The Counter-Reformation of science: how to make magnificence democratic

British research has perfected discipline and outsourced magnificence. The fix is to practise demonstration statecraft – visible proofs of capacity that pair theatre with delivery.

Recently in Rome, amid the Baroque splendour of Bernini and Borromini, I was struck again by a central paradox of the Counter-Reformation. Faced with fierce competition from Protestantism, the Catholic Church understood that discipline alone would not suffice to secure their position. It needed to impose order to curb worldly excess – but also to inspire awe to win hearts and steady the faithful. That dual imperative shaped the church’s response: tighten doctrine and stage magnificence.

Something like a reformation – a pluralism of methods, risk appetites, and time horizons – is now happening at the periphery of the scientific community, in corporate labs and new philanthropic ventures. This vitality at the edge is, in part, a response to the orthodoxies at the centre: standardised catechisms of process, homogeneous incentives and evaluative logic, timidity of aims.

Public science needs its own counter-reformation. Left as it is, it risks becoming an austere orthodoxy, procedurally unimpeachable yet gradually irrelevant to broader public ambitions. But this response can’t just be doubling down on doctrine. The counter-reformation succeeded by making the church both disciplined and luminous.

In modern science policy, in the face of equally fierce competition for resources with other policy areas, we have perfected the techniques of self-discipline – accountability frameworks, value-for-money logic, and government-mandated efficiency drives. Yet in doing so, we seem largely to have abandoned magnificence, ceding the power to capture the public imagination to private patrons and strategic rivals.

In this post, I ask whether the way back is not to weaken standards, but rather to rediscover a form of democratic splendour: demonstration statecraft that inspires awe by visibly delivering on ambitious goals.

Reformation at the periphery, counter-reformation at the centre

The pre-Reformation Catholic Church squandered their legitimacy. Critics railed against corruption, indulgences, and a faith hollowed out by bureaucracy. The Reformation shattered unity and unleashed a pluralism of voices and doctrines – exhilarating, but destabilising. Princes and magistrates scrambled to harness these movements, and over time rival confessions hardened into state-backed orthodoxies. The Catholic Church doubled down, policing heresy with ruthless uniformity while unleashing magnificence on a scale designed to restore awe. Rigour against falsehood, splendour against despair.

The parallel is of course imperfect, but there is a curious contemporary echo. Today’s pluralism in science flourishes outside the state, not within it. Non-state actors set the pace and drive diversity of method and approach. Corporate labs like DeepMind operate with fundamentally different time horizons and risk tolerances.1 Philanthropic initiatives like the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub network or Wellcome Leap pursue unorthodox approaches that public funders struggle to create themselves. The Arc Institute offers unrestricted, long-horizon support that renders most government grants bureaucratic by comparison.

Meanwhile, the public system in the UK (and much of Europe) has congealed around a central orthodoxy: standardisation not only of outcomes, methods, policy goals, and priorities, but across the whole spectrum of institutional roles and sectoral messaging, down to the very language of research.

Some standardisation is indispensable. It underpins trust, comparability, and accountability; mandates like UKRI's Open Access policy serve a vital public interest. The difficulty is a second, more problematic layer – standard practices canonised into a creed that pushes the system towards institutional isomorphism. Metrics begin to displace judgement; the proxy becomes the target. With the best intentions, we have converged on a single doctrine of excellence in science, and made it compulsory.

At the edge – in the midst of the reformation – the energy and tempo of research is different, and they are starting to reset expectations for what progress should feel like. In this comparative Wild West, new institutes are founded rather than inched into being; money can move on shorter arcs; coordination is built around unique purpose. It isn’t tidy, and not all of it will solidify into a lasting new settlement, but it has momentum. Pluralisation and fragmentation, then as now, are not defects but sources of energy. Many of today’s most exciting advances are emerging from precisely this diversity of models, not despite it but because of it.2 But the fact that the reformation of method and ambition is happening almost exclusively at the periphery has consequences for the legitimacy of the centre.

The question therefore isn't whether public institutions can reassert dominance – that ship has sailed. It's whether they can remain relevant in a world where methodological innovation is being driven from elsewhere, and avoid becoming gradually less central to the public’s sense of where possibility lives.

The Counter-Reformation response: discipline and splendour

The Catholic Church's response to the Reformation was sophisticated. They tightened doctrinal discipline at the Council of Trent while simultaneously unleashing Baroque splendour. Cardinal Borromeo's architectural guidelines demanded churches be both theologically sound and emotionally overwhelming. The Jesuits pioneered theatrical spectacle as spiritual pedagogy. The message was clear: be rigorous and magnificent.

The public sector today has perfected prudence and discipline. Long before certain corporate labs or philanthropic ventures began to pluralise and diversify the landscape, government settled into a reflex of bureaucratic rigour. Scarcity, post-crisis austerity politics, and Treasury rationalism hardened that reflex into orthodoxy. It's now heresy to discuss public investment outside "market failure" terms; ministers and their senior bureaucrats preach focus and "smart specialisation”; institutional clergy must continually dial up both efficiency and impact. What began as a sensible response to tough times has become our default way of working.

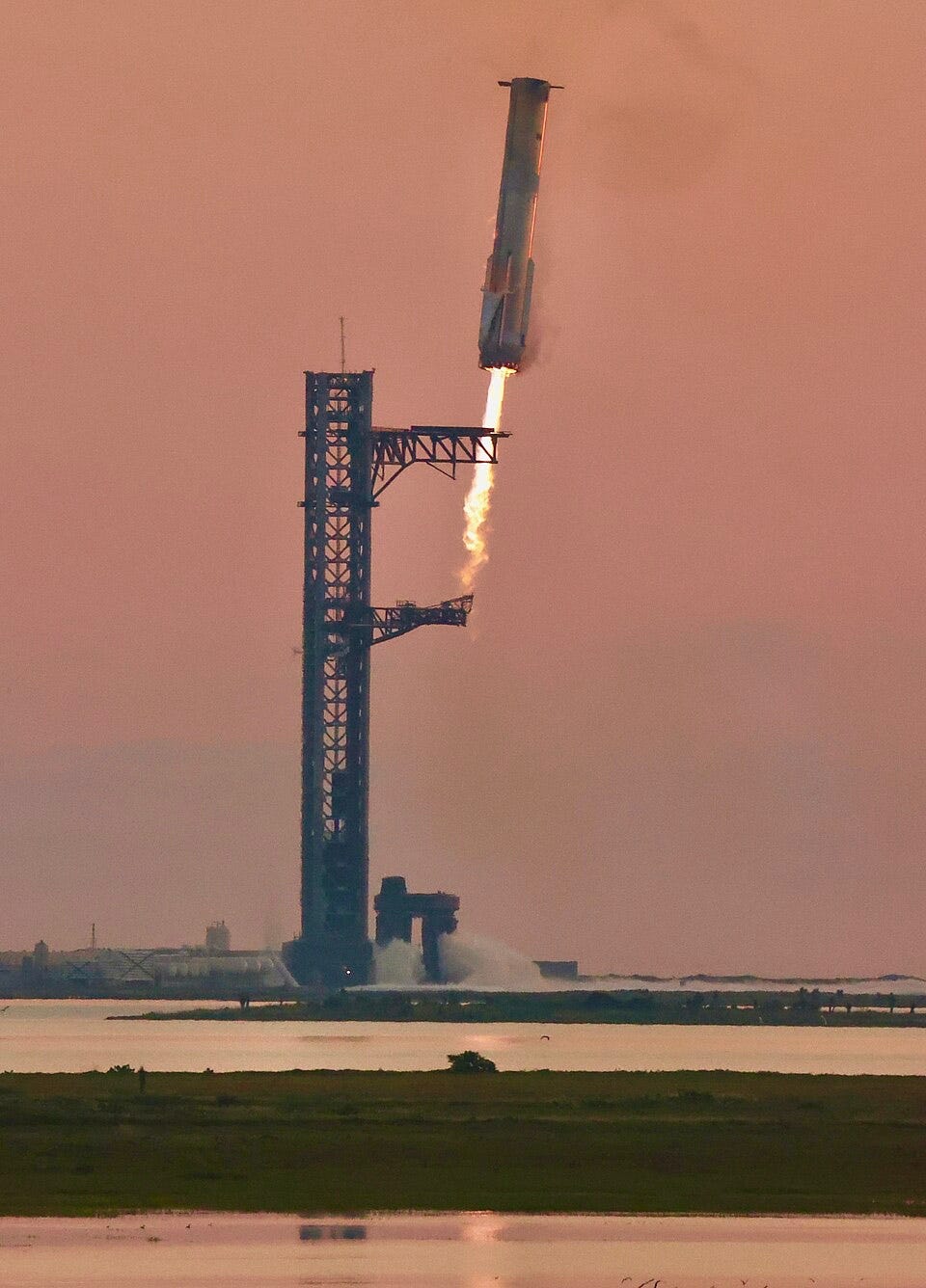

But what we've neglected is the magnificent public spectacle – pageantries of competence. When did you last see a government-funded science or technology project that made you catch your breath, as you may have when a giant SpaceX armature caught a rocket booster out of the air,3 or think bloody hell, that's impressive on a whole new level?

Authoritarian spectacle raises the bar

It’s not just Musk's rockets that are commanding attention across the globe. Authoritarian and state-capital models are demonstrating a simple equation: central patronage + visible feats = legitimacy + perceived capability. China has come to exemplify a modern form of Baroque absolutism, where central patronage combines with civic theatre. Take the Micius quantum satellite:a headline-grabbing project that set communication records while capturing the world’s imagination. Or, perhaps even more visibly, the Tiangong space station, an emblem of sovereign scientific and technological capability.

Then take Saudi Arabia, leveraging its Public Investment Fund to create a reported $40 billion fund to dominate artificial intelligence. Or the United Arab Emirates, whose Museum of the Future in Dubai is a piece of pure architectural statecraft – a spectacular living exhibit designed to signal the nation's central role in the next era of innovation.

These are not templates for liberal democracies. But they raise the baseline of spectacle against which the public makes its comparison. Our task is harder: to separate spectacle from dogma, and to build things that are visibly world-class, publicly held, and corrigible. That is precisely what demonstration statecraft is for: spectacle that proves, not spectacle that insists. Magnificence that serves both technical advancement and democratic legitimacy.

So how have we been faring?

The doctrine of homogeneity

While other nations have embraced spectacle, we have doubled down on discipline alone. In the face of increased competition for scarce public resources, a particular doctrine has come to dominate the theology of UK science policy – restraint. Treasury rationalism operates like a confessional logic, policing what counts as legitimate public investment through Green Book methodology and market failure frameworks. This creates a deep suspicion of discretionary state-building, and unlike the Counter-Reformation Church, it lacks any taste for spectacular statecraft.

This top-down dogma inevitably creates institutionalised blandness. Our research assessment processes create shared catechisms about what counts as good research. National strategies increasingly attempt to pick from a predictable menu of priorities, rather than enable diverse experiments. Even the excellent Tickell Review, while acknowledging the bureaucratic burden, focuses on slimming administration rather than enabling true methodological diversity.

This risks creating what the private sector would recognise as a dangerous monoculture.

ARIA represents a telling exception that proves the rule – the state licensing heterodoxy by statute, vulnerable precisely because it is exceptional. It exists to carve out a zone of discretion because the core system can no longer easily tolerate multiple financing modes.

The result of all of this is that ministerial speeches have a breathless quality – grand language straining against a constricting rationale. Sparkly rhetoric can never quite escape the crushing underlying logic: that government R&D exists chiefly to correct market failures and optimise spillovers. I don’t dismiss that logic; we have secured substantial investment that's both Green Book-compliant and economically defensible.

But compare this approach to the Apollo programme, CERN, or even Concorde. These were statements of grand intent that inspired generations, grounded national stories, and established technological leadership.

What would today's equivalent be? The Diamond Light Source is impressive, and its planned upgrade will make it more so, but it is not a public touchstone. The STEP fusion project is both critically important and technologically exciting, but at this early stage still operates below the radar. The last government’s botched OneWeb acquisition gestured toward ambition but lacked a coherent vision, and failed in the execution.

Does this create a legitimacy gap? The public could be forgiven for being much more excited by private rocket launches or DeepMind's Nobel Prize-winning protein folding than by anything public science produces. Blueskiers might dismiss these achievements as ‘tech bro’ dalliances, or even something more sinister. But to indulge in that kind of thinking risks us becoming scolding bureaucrats, while the new Medici capture both substance and imagination.4 With populism an ever-growing political force, it’s not hard to imagine where this could end.

Universities: the modern churches

As splendour and story drift away from public institutions, where are our beacons of hope? One place where the public can hear echoes of magnificence is in the university sector. But universities face a legitimacy crisis of their own – one of purpose. I have written before about the ugly unravelling of this crisis in the US – a cautionary tale, with ripples already felt on European shores. At its heart lie unsettled questions: are universities intended to form citizens, to educate workers, or to produce knowledge?

In a mirror of Reformation-era angst, how can the sector retain relevance? Will bloody-minded unity and ‘telling our story better’ save us? We shall see. But relevance is not narrated into being; it is built in public. By that standard, the response so far has not been equal to the moment.

This may feel like a sharp critique, so to make something absolutely plain, I am in no way saying that British research has ignored public benefit. The last two decades have seen unprecedented focus on public engagement, the rise of the impact agenda, and countless entreaties for policy relevance. On top of this, the sector has responded admirably to just about every request made of it by the government – from the COVID response to local and civic engagement.

But there is a crucial difference between demonstrating utility and inspiring awe. REF impact case studies may document societal benefit, but they're bureaucratic artifacts that few people read. Even at its best, public engagement is about creating scientific knowledge rather than creating genuine wonder. Policy relevance is important, but can emphasise technocratic contributions rather than breakthrough moments that reorient our shared sense of possibility.

The sector may be missing the Counter-Reformation lesson. Baroque churches that take your breath away weren't built to impress bureaucrats. They were designed to inspire ordinary people and demonstrate the living power of the institution.

What would the university equivalent look like? Not another business park with "innovation" in the name, nor yet another glossy and minimalist institutional rebranding exercise. The baseline is a deep commitment to being useful to their places: anchoring cultural life, sustaining regional industries, tackling local environmental challenges. Without that, legitimacy frays. But usefulness is only the beginning.

Perhaps most of all, it is viscerally demonstrating why advanced research and learning matter for human flourishing. This includes fundamental research – not with an apology, but presented instead as the mighty intellectual adventure it is.

Building democratic magnificence

From Counter-Reformation to demonstration statecraft

If we are to regain some sense of wonder in public institutions, what can our historical analogy teach us? Here I return to the idea of demonstration statecraft – visible, testable proofs of capacity that pair theatre with actual delivery.

Recent examples show the promise of this approach, and the AI Safety Summits are a near-perfect case study. The initial summit at Bletchley Park provided the essential public theatre – a global spectacle designed to capture attention and signal intent. But crucially, the trap of empty pageantry was avoided, because the summit was paired with tangible delivery: the subsequent creation of a global network of AI Safety Institutes. This is the model in action: spectacle that proves its substance by building lasting public capacity. The summit created an attention-grabbing moment of awesome ambition, while the institute network provides the enduring, useful infrastructure – a living system that ensures the initial magnificence continues to work.

Yet, for every successful example where spectacle is tethered to substance, history offers cautionary tales of hollow grandeur for its own sake. Consider the Superconducting Super Collider – a spectacular physics project that consumed $11 billion before cancellation, leaving only abandoned tunnels in Texas as monuments to mismanaged ambition. Or look at ITER – at high risk of becoming a "cathedral" that consumes resources for decades without delivering promised fusion power.5

The Apollo programme worked because it combined genuine technical frontier-pushing with public purpose and visible progress. The magnificence was inseparable from the achievement – you couldn't fake landing on the moon.

Part of what made that possible was the state’s willingness to shoulder risks others could not. Public institutions have always had a particular calling here: to fund work with long horizons, high uncertainty, and diffuse benefits that markets would never touch. In recent years, however, this role has become blunted. Layers of managerial oversight have made risk itself feel like recklessness, rather than the necessary condition of progress.

The challenge for demonstration statecraft, then, is not to eliminate risk, but to structure it so that democracies can sustain it. Magnificent projects will always carry the possibility of failure; what matters is whether they are designed to fail safely, adapt, and keep public trust. That requires a rhythm: something tangible must appear within twelve months, not as a finished cathedral but as a visible sign that the work is real. From there, the story must be told and retold, each year adding scale and splendour, punctuated by moments that feel miraculous. In the Counter-Reformation, this was the role of Borromeo’s rules, Loyola’s Jesuits, Bernini’s sculpture – repetition, pedagogy, spectacle. Today, demonstration statecraft also needs its priests and saints: figures who embody the story, keep awe alive, and show the public why the risks are worth taking.

What living magnificence looks like

Now to the heart of the puzzle: how do democracies create awe-inspiring projects without becoming reckless, or falling into technocratic capture or authoritarian gigantism?

Democratic magnificence requires different institutional architecture than normal government programming. There are lots of ways to achieve this – and, again, ARIA is demonstrating its willingness to do things differently with its network of “activation partners”. Sometimes it’s simply about better project management – where major research projects are required to pass through gateways and have exit strategies in place from the start, and with sunset clauses that require explicit ministerial or parliamentary renewal. The goal should be to structure projects so they can make bold commitments while remaining answerable to public judgement through concrete deliverables, rather than bureaucratic processes, preventing white elephants while allowing genuine long-term commitment.

Magnificence cannot mean outspending autocrats, billionaires, or multinationals; in the current fiscal context, that would be an unaffordable luxury. Democratic magnificence instead has to out-manoeuvre with different virtues: ingenuity, openness, and civic purpose. The task is to create things that others structurally cannot: projects whose spectacle comes from transparency, whose value is measured in public benefit, and whose legacy is a more capable and engaged society.

What follows are some ideas, intended as food for thought, of what this living, democratic magnificence could look like.

Visible, functional infrastructure: A quantum computing facility designed as a public forum, where citizens can not only witness experiments but also meet the physicists, postdoctoral researchers, and technicians making it happen. A life sciences institute integrated with NHS clinics, where patients benefit from cutting-edge research they can see happening. A laboratory for the future of entertainment that doubles as a testbed for advanced communications technology.

Missions as public theatre: Fusion demonstrators where the public can follow the work of a specific team, see their trials and errors in real-time, and understand the human drama of invention. Biomanufacturing campuses that produce medicines while training the next generation of biotechnicians. Climate infrastructure that's also a citizen-science platform – tidal arrays where school groups can monitor marine ecosystems. Museums and media that bring science to millions every year, inspiring the young.

Institutional magnificence: Universities designed for public engagement where citizens can witness discovery in progress. Research institutions as transparent engines of knowledge creation, not ivory towers.

And perhaps some demonstration statecraft rules of thumb:

Visible within twelve months. By the end of month twelve there is a thing the public can see, touch or use: a pilot service running in one NHS trust; an operating prototype on a rooftop; an online tool that thousands of citizens have tried. It does not need to be finished, but it must be undeniable.

Legible end to end. The path from input to outcome is visible. You can sketch it on a single page: where the money goes, what the system does, who benefits and how risk is handled. Publish an explainer, a process diagram, and some metrics. Release a small open dataset or an API so that outsiders can poke at it and learn.

No empty cathedrals. As with any statecraft, demonstration statecraft should work in stages with hard gates. If a programme passes a gate, it scales; if it fails, it exits cleanly with a published post-mortem. Put exit ramps in the plan and in the contract.

Dual use for capacity. Every demonstration should leave the system stronger even if the headline fails: researchers trained; technicians promoted; tools and software made reusable; and procurement frameworks others can adopt.

Alchemy of translation. Curiosity-driven research does not automatically inspire awe. It often requires mediation – the “alchemical laboratories” of museums, galleries, exhibitions, or digital platforms that turn abstraction into public wonder. Demonstration statecraft must build these bridges deliberately, not leave them to chance.

Finally, we must not forget the aesthetic imperative. This stuff has to be beautiful. Architecture and design matter. If you're asking the public to support ambitious science, show them something worth supporting.

Building capacity alongside spectacle

Of course, building spectacular infrastructure is not the whole answer now, just as it wasn’t in 16th century Rome. The impact of the Counter-Reformation included the seminary system, new educational orders, and standardised training that raised baseline competence across Catholic territories. Perhaps modern science needs something similar: spectacular missions accompanied by unglamorous but essential capacity building.

To my mind, this means graduate schools designed as talent pipelines that serve the whole system, not just the education of individual scholars. It means creating proper technician career ladders that create skilled workforces.6 And it means embedding open methods and standards that raise competence across the entire ecosystem.7 The visible missions get the attention, but the boring institutional work makes them possible.

This connects to the most important asset in public science. For any policymaker who has toured government-funded labs, the most singularly impressive feature is not the infrastructure, but the people: the driven, bold, and creative individuals pushing the frontiers of research and innovation. Demonstration statecraft must have brilliant people at its heart.

Rome's lesson: magnificent infrastructure

Rome’s first lesson is that magnificence endures when it is anchored in living systems. Counter-Reformation churches solidified allegiance to the faith not only because they dazzled, but because they served active civic and religious life: spaces of worship, community, art, and organisation. They inspired because they worked. Our goal should not be to create beautiful ruins for future generations to admire, but rather thriving scientific cities lit by purpose.

The deeper lesson is one of integration. Rigour was not a brake on ambition, but its companion: doctrine tightened, but turned outward as boldness and splendour. Counter-Reformation Rome did not shy away from bold commitments: it commissioned works whose scale could have bankrupted popes, and sent missionaries into dangerous new territories. In a democracy, risk cannot be unlimited; it has to be structured so that it builds trust rather than erodes it. Magnificent projects therefore need to be both ambitious and adaptive: able to fail safely, evolve as knowledge changes, and remain visibly accountable to the publics who fund them. And accountability here means more than audit trails – it requires legibility. People must be able to see and understand what is being attempted, and why. This will require a reform in how we think about and present science to the public: making it legible, ambitious, and beautiful.

We cannot turn the clock back, any more than the Popes could once Luther’s theses were nailed to the door. Nor should we wish to. The question now is what the Counter-Reformation in British public science will look like. It can retreat inward – clinging only to procedure and discipline, gradually fading into irrelevance. Or it can re-enter the world with purpose and splendour: a civic project that builds visibly, welcomes scrutiny, and enlarges what people believe is possible.

Not all industrial R&D is like this, but there are enough examples to indicate a growing trend.

Pluralism, of course, carries its own risks, and I’m not arguing that every corporate or philanthropic venture is sound. But methodological diversity itself generates vitality – which is precisely why public institutions matter, to anchor standards while also finding their own way to inspire.

There are some examples, and we should learn from them. The James Webb Space Telescope is one. The Oxford COVID vaccine is another.

Although I have framed this argument around science and technology, the same pattern is visible elsewhere. In health, Gates Foundation funding has reshaped global public health priorities around infectious disease and vaccines, often outspending the WHO. In media, Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter/X shows how a single wealthy patron can reconfigure global communications infrastructure in ways that dwarf national regulators. In education, the rise of philanthropic “charter networks” in the US – or initiatives like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s Summit Learning platform – has challenged state monopolies in curriculum and delivery. Each illustrates the same dynamic, where private patrons combine capital and spectacle to reset legitimacy.

I very much hope to be proved wrong about this.

Note, raising competence is not the same as enforcing uniformity.